The Winemaking Tradition

In the early 70’s, I attended a family wedding, which included my great Uncle Tony (Zio Nino) Diecidue at the table. Zio Nino, who was known as a master winemaker in Tampa, spoke about the family’s winemaking tradition that spanned back to Cianciana Sicily. I had vague memories as a child, of the men getting together at the Diecidue home in Ybor City each year to crush numerous cases of California grapes.

In the early 70’s, I attended a family wedding, which included my great Uncle Tony (Zio Nino) Diecidue at the table. Zio Nino, who was known as a master winemaker in Tampa, spoke about the family’s winemaking tradition that spanned back to Cianciana Sicily. I had vague memories as a child, of the men getting together at the Diecidue home in Ybor City each year to crush numerous cases of California grapes.

The house had a special garage-type building used only for winemaking. Although we had enjoyed Zio Nino’s homemade vino for years, I had never actually made wine with him. In fact, he revealed to us at the wedding that hardly any members of my family were participating in this traditional event. When we left the wedding that evening, I thought about how tragic it would be for this family tradition to end with Zio Nino.

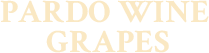

That October, my father and I went to help Zio Nino make wine. I spent several days experiencing an extraordinary blend of folk science, tradition, superstition, and being yelled at numerous times (maybe constantly) for asking too many questions.

I observed this usually gentile man become a meticulous tyrant making wine, and rightly so unless you wanted to end up with the ultimate infamnia…aceto (vinegar). The floor and the walls of the large structure had been sanitized, the equipment had been sanitized, and by the time we finished, I’m sure that we were sanitized.

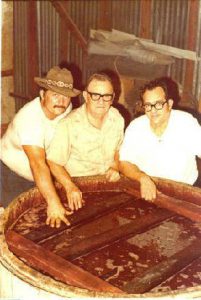

Zio Nino was very specific about every step of the winemaking process, from how the cases of grapes were unloaded from the truck, opened, and stacked; to ensure that the grapes were the correct temperature when they were crushed; to loading and tightening the wooden presses and filling the barrels and jugs with the juice that flowed from them. During the days of my first winemaking experience, I observed other winemakers bringing him samples of their wine from the previous year. Most would ask his counsel on how to improve their wines.

They asked about making it sweeter or dryer, why it turned cloudy during the year, why it turned to vinegar, and other questions, in order to improve this year’s wine. Uncle Tony had a shelf full of wine samples brought to him by these men, each labeled accordingly. I was impressed with their respect for his knowledge and experience. I later developed even greater respect when I began reading about winemaking and realized that there were valid scientific reasons for almost every meticulous thing he did. When you empty a wine barrel or large jug, you do so by siphoning out the clear wine just above, and leaving behind, the sediment that was produced during fermentation.

Zio Nino once told me that this siphoning (called racking) should be performed on a clear cold day, to ensure a clearer wine. It was one of the few processes that he wasn’t sure why it worked, but it did, and the family had followed the practice for years. Later, I read that when you rack your wine on a clear cold day, the barometric pressure is such, that it holds down the sediment, making it less likely to be sucked up into your hose, and therefore, making the wine clearer.

However, the claim that eating marinated sarde salate (salted sardines) preferably from Sciacca, Sicily, with a glass of last year’s wine, would ensure a good new wine, has never been substantiated, but we still do it every year.

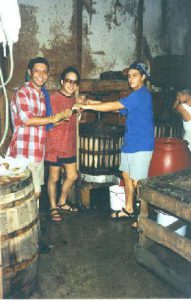

My father, Jimmy (Vincenzo) and I made wine together every year since that first experience, usually with Zio Nino. Today, the annual tradition continues with my son Vince (Enzo), his daughters Mia and Stella, and son little Vincenzo.